A Quick Description of Benford's Law with respect to Election Fraud

A couple of weeks ago at dinner with friends, I brought up how how some social scientists think we can analyze the way digits are distributed to uncover election fraud, but was unable to articulately explain it to my dinner companions. So, I wrote up a a quick thing help show what I meant. So, in this post, I’ll describe Benford’s Law (which is what the natural distribution of digits is sometimes called), show it mathematically (don’t worry, it is quick) before showing what it looks like graphically and then doing a quick analysis to see if the 2012 Minnesota Senate election fits applies to electoral results.

Benford’s Law, which according to Wikipedia is also called the first-digit law, `states that in many naturally occurring collections of numbers the small digits occur disproportionately often as larger digits.’ In other words, smaller digits show up more often in numbers than larger digits, or one shows up more often than nine. Theoretically it can be applied to all digits in a number, but practically most people usually use it to examine the occurrence of first digits in a series of numbers. So, if we have the numbers 132, 191, 323, and 434 we would see that there is one instance of three, two instances of one and one instance of four as the first digit. Like I said, though, we could do this sort of counting with any digit place in the number (like focusing on the second or third digit places). Many types of numbers fall according to this pattern. House numbers in a city, monetary transactions for a business (so Benford’s Law can be used to detect fraud), and occasionally election results. Mathematically, Benford’s Law is (usually) described using the equation in equation one. I say usually because it does not always need to use base ten logarithms, but most uses of it do.

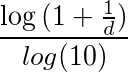

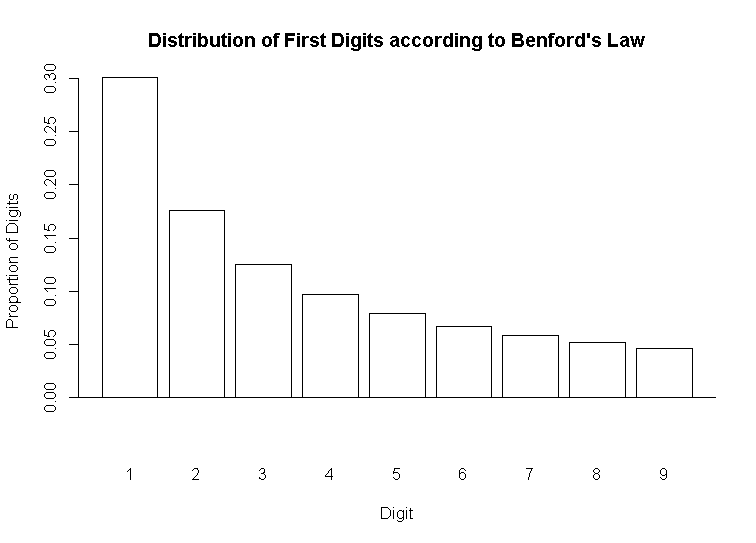

And if we plot that equation, it looks like the plot in Figure 1.

To reiterate, according to Benford’s Law, if we collect all of the first digits in a series of numbers, sum them up, and calculate the percentage of the first digits that a number represents it should follow the pattern in the graph. More concretely, if we collect all the first digits in a series of numbers, about thirty percent of those first digits should be one, around 17 percent should be two, and so on (as an aside, this distribution is an example of a lognormal distribution. Another set of things that follows this type of distribution is the size of cities. That is, there are many more smaller cities than bigger cities.). The logic goes that if we collect a real life series of numbers and the digits differ greatly from what is theoretically predicted, then there is probably something amiss with the real world data.

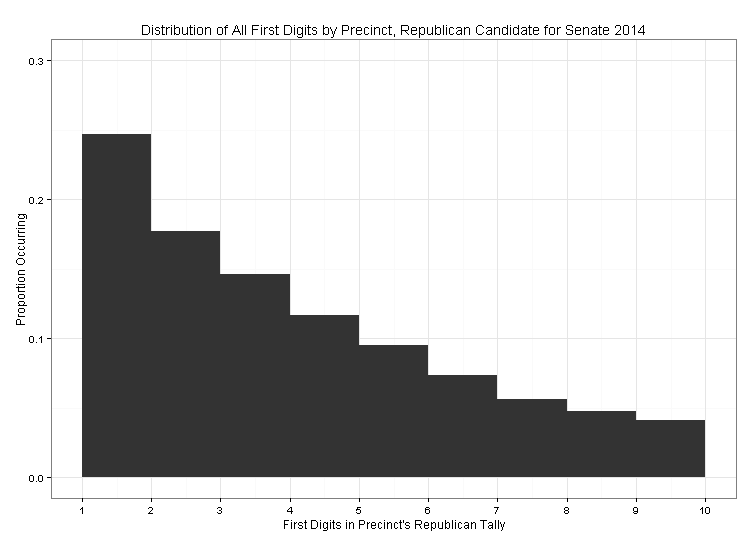

To that end, and to illustrate this point, I am going to use Benford’s Law to see if the distribution of digits in a recent American election sync up with what Benford’s law predicts. Specifically, I am going use Benford’s Law to examine whether or not the distribution of Republican votes in the 2012 Minnesota US Senate Race fit with what we would expect, given the distribution described above. To do that, I collected all of the precinct level election results for the 2012 Minnesota U.S. Senate election from the Minnesota Secretary of State’s website. This resulted in the election results for 4107 precincts. As an example, the first five precincts in the data had 324, 238, 48, 9, and 5 votes for the Republican candidate. From there, I collected just the first digit from all 4107 precinct’s Republican tallies, summed them up and created the plot below to show their distribution.

If we compare the plot of actual data to the theoretical data in figure one, the form looks basically the same. The ones are slightly suppressed with respect to what they should look like, theoretically. It seems very unlikely that the Republican vote was systematically tampered with in any way (through either nefarious or erroneous means). If it were Iran or some place with a history of corrupt election administration, we might see the plot flipped (as in 30 percent nines, 17 percent 8s, etc).

If just eyeballing the data isn’t good enough for you, there are statistical tests we can do to more rigorously compare the observed data to the theoretical data (for instance, a chi sqaured test would work) but just eyeballing seems good enough for this demonstration. If you go into the github repo used to generate this post, I included some code and a package someone built to conduct a more rigorous analysis using Benford’s Law.

(you can view the R-code I used to generate this post here. I relied on this blog post to create the theoritical plot without generating fake data.